I was a Navy test pilot at Flying Qualities and Performance Branch, Flight Test Division, NATC Patuxent River from 1968 to 1971. We did it all – If it had a fixed wing and a tail hook, we tested it. It was our branch that wrung out captured Soviet aircraft at obscure locations in Nevada, we did spin and out-of-control work with carrier-based aircraft, and we did all kinds of more mundane aircraft testing. Some of it was done at NATC, and some was done “on the road” at the contractor’s own facilities.

Look, some of this stuff was pretty ordinary – and some tests seemed to drone on and on. In January, 1971, I found myself grinding away at LTV Dallas trying to get a handle on something called Seek Eagle, which involved performing and evaluating some pretty high-g maneuvers in the A-7E airplane. The routine was that I would go out on the range and do the maneuver, then relay my qualitative impressions to base. “Base” was a small LTV communications facility that received real-time data from the test airplane as well as lots of verbal inputs from the test pilot. Sometimes I would do the talking during the maneuver, but talking at 6g’s could be a bit strained.

Flight ELEVEN was coming up, for crying out loud. Still no end in sight. I had noticed early-on that the Flight Test Engineer, Ed Hardesty, manned the base and spent his time copying our entire conversations by hand – legal pad and pencil! Even though some of the control inputs were deliberately ham-fisted, the bulk of the conversations were aerodynamics-techie stuff. How does that get done with just pencil and paper? When I gave him a questioning look, I got a long dissertation about how he ALWAYS got ALL of the conversation without missing a beat. Don’t trouble your little heart, DD.

Well OK. I mean, it seemed a bit like a challenge to me. My feeling was that we needed to do something to up the pace. So … that evening I spent some time fashioning a nonsensical spiel of aeronautical gibberish to feed him on Flight 11. As long as we’re testing things – let’s take a look at his stenographic skills!

Morning came and I blasted into the wild blue. I had carefully transferred my phony comments to my kneeboard pad. I couldn’t wait for the first maneuver!

It went something like this (my call sign was Cobra II):

Engineer: “… Your static margin is 1.8.”

Cobra II: “Got it. Some comments on maneuver #1. Once reaching 500 KIAS and hammering on the g, I …ah… got some lateral, ambidirectional vicissitudes that resulted in quasi-perturbations, initially curvilinear then asymptotic to the force gradient.”

Engineer: “Whaat? I, ah … broke my pencil! Run that by me again, Cobra.”

Cobra II: “You have spare pencils, Ed?”

(Long pause)

Engineer: “OK. We’ve sent a guy for a dictionary.” (Long, long pause.) “Cobra, if you would stick to the more accepted engineering terminology, like ham-fisted instead of vicissitudes, I think we could handle you a little better.”

Cobra II: “Roger.” (Big grin!)

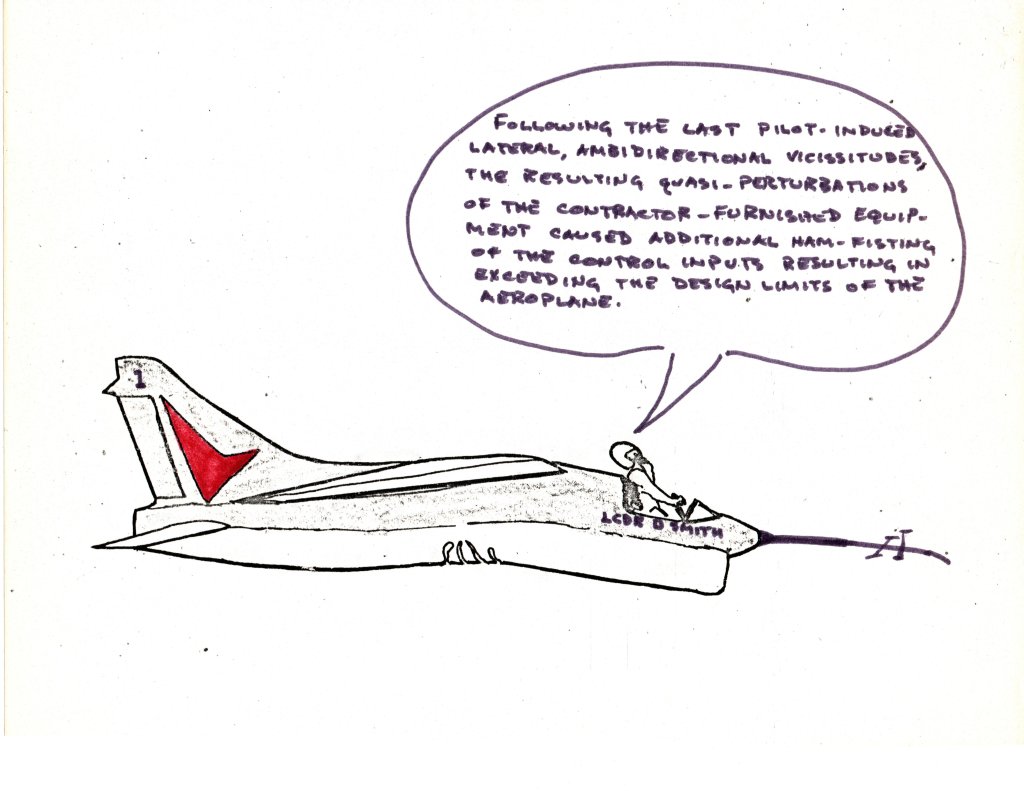

It wasn’t long after returning to NATC that I received the enclosed sketch. I know it’s a little hard to read, so here’s the quote:

“Following the last pilot-induced lateral, ambidirectional vicissitudes, the resulting quasi-perturbations of the contractor-furnished equipment caused additional ham-fisting of the control inputs resulting in exceeding the design limits of the aero plane.”